So this year, I’m taking part in National Novel Writing Month again. Last time, completing it caused such a high, setting a target, reaching a goal, it was exhilarating. So, I’m doing it again. I’m taking advantage of the time and space and bandwidth to be able to do this and I hope you like what you read so far.

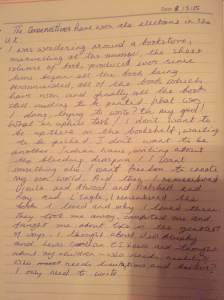

Comments are invited, I’m going for something completely different to last time’s effort and reasons are explained in the picture.

Suva. Beginning somewhere near the end.

Snowfall, like paper confetti. Pristine flakes, the size of 50 pence coins. Tips of noses cold to the touch and hands wrapped inside mittens, warm as hot buttered toast.

I long to be inside, inside the warm where the fireplace casts red and orange lights on the walls of the room.

I long to hear the stories again.

My name is Suva, I have white hair, the colour of the dirty snow before it melts away into nothingness. My eyes are brown and still clear, although their lids are hooded. My skin falls in folds and wrinkles and I find it difficult to walk when the cold sets in. I am thankful that my mind still holds pictures and words and moments which have come to define who I am today. Today I am more than I was and more than I am, but much, much less than who I am yet to become.

Before I leave, I need to tell you a story. I was not brave enough to tell it before. Perhaps it would have been of some comfort to somebody, but then again, perhaps nothing would have come of it and I would have been called mad. But now, in the few months I have left, sanity is not the thing which eludes me. It certainly is not the thing I most care for. No, I care for the memories, those wonderful moments which I need to share before they are locked in the sky forever, when I leave. For the sky sees but only whispers to the ones who will not tell.

When I was three years old, or there about, I would hold my father’s index finger and we would walk to the shops as he bought the things he needed. Usually they were cigarettes; slender white sticks which when lit, made grey clouds swirl above our heads as we sat and played. The tip would glow red and I would watch mesmerised as they became horses and eyes and hearts and hands. As I grew older I would imitate him with the white candies they sold as kiddie cigs. I would take a long drag, as I held the candy to my lips and then lick the sweetness as I blew out nothing but sugared breath from my mouth. But the tip would not glow red and there would be no grey clouds swirling like dragon’s breath.

As I grew older still, too big to sit on my father’s lap, I learned to cock my head in the same manner as him, when he listened to my stories. In turn I would listen to his stories of the clouds which spoke to him as I slept during sultry afternoons, just before the storms hit. He said, they said that they wanted to dance and they needed the chorus of the rain to keep time as they banged on their drums and rumbled with kathakali heels in the sky. He said they would transform with great flourish into men and women, gigantic, dark and beautiful, half formed, only to dance. And they would speak only to him, because he was the only one who listened.

Stories were a significant part of my relationship with my father. He left, they said ‘died’, when I was only nine years old. I missed him terribly but we met again soon afterwards. I would save my stories for him and as a consequence the people who remained with me, worried that I had grown quiet and sad. They worried that I was not the same as I was and that the loss had affected me too greatly.

My mother grew sour and hard and she did not have time for my stories, as my father had. She was young and beautiful and soft and curious, before he left. She is young and beautiful again but she occupies her own space, a quieter space where she sleeps mainly and wakes only to kiss me and sing me goodnight.

I see you raise an eyebrow. I see you splutter and spit as you sip your tea. But you needn’t. And I don’t mind. Stories need to be told. It does not necessarily mean that they need to be believed, because, as in all things real and true, they remain so, whether we choose to acknowledge them or not.

Let me tell you my story.

***

Kytö

As I read I smiled. It seemed like the beginning of a wonderful story. My father gave me his great grandmother’s diary, written on paper, which was now yellow and brittle. The ink was blue and faded but still very legible. He said it was how people used to document things. I knew this of course, being an ‘almost’ Antiquarian, but he needed to tell me, nevertheless. I knew that even in her time, many had stopped using paper and ink, so this was a rarity to say the least. I had seen paper diaries before, in museums, as holograms and physical objects only behind glass. We had watched our tutors handle real books with gloves, folding over the leaves, one by one and I had assumed that one day I would be able to do the same. But truth be told, someone of my status would have to wait a very long time before I had the opportunity to officially handle a book. Which is why, I suppose they intrigued me even more.

These days we used voice command and thought transmission. Documents were virtual and eternal, they could not disintegrate, crumble and fade like the yellowing leaves of the diary. Although, with changing technology, the challenge is and always will be to save in a format that is easily convertible to whatever will come next. Technology does not stand still for long, I suppose.

The book was a comfortable weight in my hand, about 200g and was about 25x20cm, in dimension. As I gingerly leafed through the pages, I saw the handwriting change. I ran my fingers over the fading script and could still feel the impression the pen had made, and I imagined my great, great, grandmother’s face as she silently and physically willed the words to appear in neat parallel lines. An electric thrill passed through my upper body as I realised what I was holding. It was so much more than the actual words written. I was holding a piece of Antiquity.

The printed word could only be found in signs now, instructions, labels and commands. To write, to have words which expressed thought and emotions, just for the sake of them was rare, if it existed at all any more. I did not possess a single pen or a scrap of paper in my home and I could not think of who did. I did not learn how to write. And typing, well, we do that as a last resort. We do not need to type, let alone write in our time, of course. So, this indeed was a wonderful gift from my father on my twenty-first birthday, I was grateful to him for this rare thoughtfulness.

I enjoyed Antiquities, as a subject at school and I had taken it as my chosen field. I was branded as an eccentric and a romantic. What could I, Kytö, possibly do with a degree in History and Antiquities? I did not know. And I really did not care. The past fascinated me and transported me to a world I believed was much kinder. A world which had more time. Although, when I thought about it, there was not any unkindness in our time, as such.

Regularly I would sit in the visualisation chambers of our department and choose an era. On my course, there were many like me but we did not interact much with each other except when necessary. The concept of friendship is not so popular in our time and died out during my father’s generation, I think. It is far more efficient to interact only for class, work and mating, and even then, these days, if I wanted a child, I would be able to go to the bank and wait to be impregnated. Our emotional or physical urges could be taken care of quite easily with our technology. We had become more insular and self-sufficient. This was how things worked.

I held the book in my hand once more. I held it up to my face as I have been told that books of a certain period have smells and I was not disappointed. It was a heady feeling, I shall admit. The odour was slight and yet distinctive. There was a certain organic warmth to the smell, I could not describe. It smelled alive, I suppose is the only way to explain it, although that would be inaccurate.

I was transported, let’s say, to somewhere other than here and it was not an unpleasant feeling.

***

Suva. Diary

I haven’t always kept a diary. I started when I was about nine years old and then I stopped. I had others to talk to by then. Others to keep my secrets. Writing things down in books was for when I was alone. Now it is for when someone else might be alone. The thing is, there really is no need for anyone to be alone, not when they know what I know.

When my father died, I lay in my mother’s bed. I tried to hold the woman who lay still and rigid. Occasionally, she would convulse with involuntary sobs, which she tried hard to muffle with her pillow, but we could not escape her grief. I was there because she asked me to be there for warmth and comfort for both of us, but she had already begun to turn cold. Something inside her had begun to harden and it was not until much later that I understood that my father had torn away a piece of my mother’s heart. Perhaps it was caught somewhere, hooked to his own.

The next day, I opened my eyes as the sun half-heartedly filled the room. It was a grey light of dirty clouds and half rain, and I remembered where I was and why I was there. I did not wake my mother. I wanted to get away from her, to escape for some time. The sadness she wore like a perfume, overpowering in its heady scent made me feel nauseous.

I padded to my own room, barefoot in pink pyjamas and pigtails, holding on tightly to my own tears as I walked. The absence of my father was not so present here. It was where I spent my time alone. I dug through my shoe box of secret things and took out what I was looking for. It was a diary from last Christmas. I had not written in it because there was nothing I wanted to write. I had no need to write. All that I wanted to express, I did to my father. But today there was no father and I needed to say what lay so heavily on my chest.

“Dear Diary,

I am so sad. My father is dead and there is a something heavy in my chest. I feel like I will have to carry it around forever. My mother is very sad too and I don’t know how to help her. Maybe sleep will help. But then she’ll wake up, like I did and she will remember that Daddy isn’t here anymore.

Suva”

And so this is how it went. I would write down how I felt, because I had no one to tell it to. It was during the summer holidays so school could not be of help. My mother became more and more withdrawn and I found myself caring for her when all the relatives had left. Her sister stayed behind and offered to take me with her. My mother refused.

“She is all I have left of him. I want to see his eyes in hers but I can’t bear to just yet,” she said.

And so we were left alone.

I wrote in my diary as I watched my mother fade. She would give me food and shelter and warmth. I was clean and healthy. The house was spotless, the beds always made. But it was as if she was turning from colour to black and white. Eventually the picture would melt away into the backdrop, I feared but there seemed to be nothing I could do.

And then I finally saw it….”

***

Kytö flipped through the remaining pages of the notebook. They were blank. He went back to the first page and re-read the lines. They remained, blue, faded, intact. The rest of the pages carried only confusion in their emptiness.

Eyes closed, Kytö willed the words to reappear. It was silly, he knew but it was a habit he had not yet learned to break. Wishing, hoping, giving the world time to rearrange itself for some sort of magic to happen. He opened his eyes again, turned the pages and still there remained nothing.

Perhaps, perhaps, he thought, the ink had faded, reacted to the light, a simple physical process. That was that, then, a relic and actual piece of Antiquity, gone forever.

He wrapped up the diary and placed it carefully in the case it was packaged in. He walked over to the vacuum sealed safe he had purchased a few months ago, in the hope of beginning his own collection of Antiquities and he sat down facing the window.

An orange light began to bleep, just out of his eye-line and without thinking he willed the machine to play.

“Meeting reminder in thirty minutes. Rosewood Hall of Sanctuary Campus.”

Willing himself up from his seat, he picked up the communicator which lay on the table of metal and fibreglass. He placed it on his wrist. He could not yet bring himself to have one implanted yet, although he knew he would have to succumb in a year or two, as the old devices became phased out.

Looking back briefly at the vacuum safe, Kytö sighed and left his quarters.

The sky outside remained a steady two dimensional blue. It would be dimmed artificially, to orange to red to purple to black, as day wore on. The weather had ceased to be an issue, ever since the 100 year dome was installed. All the major cities had one and soon the smaller towns would also have one installed. The skies were always the way they should be with the dome.

Before the dome, Kytö remembered the brooding skies, fortelling of thunder storms, he remembered the pricks of drizzle, at the time cold and a nuisance, he remembered the scorching sun on the back of his neck…there were no longer extremes, only temperance and Kytö could not help but swallow hard on the realisation that he would never feel too cold or too hot again.

He walked on. Rosewood Hall loomed large and he entered five minutes before the scheduled meeting time. A vending machine stood in a corner of the lobby, outside the meeting room and Kytö helped himself to a coffee. He pressed for a breakfast pill and was pleasantly surprised as the machine dispensed one immediately, without its usual fuss of error lights and messages.

He swallowed his pill, he sipped his coffee and entered the grey blank room which held a conference table and ten chairs neatly placed around it. Two others were already seated on opposite sides of the width of the table, silently looking past each other. Glancing briefly in Kytö’s direction, they showed no recognition even though they had met countless times. It was this, this coldness Kytö could not fathom, could not be a part of. Indiscernibly he shook his head as he sat down and waited for the fourth member of their group.

She arrived late, after Kytö was sure he had dozed off with his eyes open. No one spoke until Layla entered.

“You’re five minutes late, Layla,” one of the members said.

“I know. I’m sorry, I overslept!”

Layla sat down, next to Kytö and smiled. Kyto breathed it in, inhaled as if he had been suffocating earlier.

The meeting was called to order, formally by Drake who led everything, who knew everything and Layla and Kytö nodded and agreed and updated the group on their progress.

It was a dull undertaking. Layla reported that she was making steady progress with the translations and Ban recorded it on his recorder. Ban also said he was making steady progress on the restoration of files, although some were proving more difficult than others, he would pass them on to Layla, as soon as they were done. He suspected that they were probably corrupt, incorrectly saved. Kytö reported no new findings, nothing of interest in the interpretations of the translations, which he received from Layla. The files were of simple telephonic exchanges between normal everyday people. Nothing political, no new insights, it was all rather tedious and that he did not see the point of it. Drake glared and said that he had uncovered new files which needed restoring and translating and interpreting. He trusted that Kytö would still be interested in the work, or perhaps Drake should look for a replacement. Kytö assured the team that he was very grateful for the opportunity and would be glad to continue.

***

“Fairies don’t exist! You’re making it up!” Bella was a small girl with straight dark hair and long dark eyelashes. She was quite bossy for her size and spoke about boyfriends and television shows Suva was not allowed to watch. She drank fizzy drinks and ate chips. She was impossibly beautiful in Suva’s eyes and knew more about the real world than anyone else their age. Suva knew Bella would not believe her, as soon as the words left her mouth, but who else could she tell? Her father was no longer with them.

“I know what I saw. I know they were there.”

Since the move back to India, at her grandmother’s insistence, Suva felt even more out of place. The good things, the things she liked were the birds and the stray cats and the blue skies. She did not like the maids, the way her mother just languished on her bed, the way her grandmother remarked at her dark skin, dark like her father’s. She did not like her grandmother’s gnarled fingers pulling at her hair to tie and tame into plaits which left her with waves which never fell flat like Bella’s. She liked Bella and her new school but she did not like the homework and the boys. She missed the quiet and peace and how her parents were her own, how even when her mother was at her lowest, she was still, her own. Now her mother was a woman who lay on a bed all day who did not want to be disturbed.

Suva used to run away, refused to be watched by the maid who was paid to watch her. She would run out of the gates to the forest behind their complex and watch the birds as they flitted. Parakeets and Mynah birds, sparrows and crows. They ignored her, paid her no special attention and then she saw them.

She thought they were dragon flies. Flying insects, with long bodies and strange limbs but then one landed right in front of her, with arms and legs and a face. She was not afraid, as he looked at her, as he bowed.

Suddenly he flew up into her face, causing her to shut her eyes. He pinched her cheek and flew away.

She did not dream it.

She was in the forest behind their complex and she was wide awake in the green, golden afternoon haze. The koyel was calling as the sun dipped lower behind the hills in the distance and Suva smiled, more certain than ever that she did not dream it.

***

Kytö opened his eyes. When did he fall asleep? In the room, it was still the same and yet he could remember the words, just out of earshot and he could see the green golden light of the forest, of the jungle, he thought would be more accurate, behind the complex he never knew existed.

Goosebumps formed on his skin as his mind tried to make sense of something which refused to be made sense of. Drake was still talking. Layla was still next to him and Ban was still recording.

“Did I doze off?” Kytö typed out to Layla.

Layla felt the wristband vibrate and looked down. She looked at Kytö and gave him a smile laced with a question.

“No, why?” she typed back.

“It doesn’t matter. Will you have coffee with me, later?”

“You’ll have to wait and see.”

The minutes melted into the afternoon and Drake finally called the meeting to a close.

Kyto and Layla rose wordlessly from their seats and headed to the exit. Outside, the light was the same as it was when they went in. Sunsets and sunrises could be viewed from special paid gallery. It was the same place where constellations could spotted and identified. In the real world, Kytö’s and Layla’s, the light came on in the mornings, at an appropriate time and was turned off night. All citizens received the appropriate amount of daylight, year round to combat depression and consequent suicides.

It seemed to be an efficient way of doing things, suicides were unheard of now, although occasionally, one might encounter a whiff of something suspicious.

“So, coffee…that’s unorthodox” Layla’s voice reached through Kytö’s thoughts and nudged him awake.

“Yes, I can see how you might view it that way, but it’s what would have been normal, say two generations ago?” It was a timeframe, Kytö was trying to verify with a fellow antiquarian.

Gently, Layla took Kytö’s hand, as they walked towards Kytö’s apartment.

***

Suva ran home, her braids thwacking against her shoulder blades as she raced through the forest. She manoeuvred her way through the roller skaters who were practising in the empty space between the tennis courts Suva could not enter.

Night had fallen and the blackness which filled the night canopy was interrupted at regular intervals with the white sodium glow of lamps on every corner and every few hundred yards. A kind of innocuous gloom followed Suva home. Inside the apartment, with the curtains drawn and yellow lamplight Suva tasted her evening meal and did not taste it at the same time. Her grandmother’s angry mutterings fell like dead moths, fluttering, twisting, helplessly to the floor. Suva made her way to her mother’s room.

The bed looked empty at first but the sheet, crumpled in a heap, moved imperceptibly up and down, revealing a breathing corpse perhaps. Suva had begun to see her mother this way but occasionally the corpse responded with a grunt, sometimes even a word, and Suva hoped she would respond tonight, as there was no one else.

“Mama, I saw something in the forest behind our building. I know I shouldn’t have been there, but Kajol Didi was annoying me so much and Dida was telling me off for wearing this dress, that I had to run away.”

There was no reaction. The corpse continued to move up and down.

“Mama, I saw a fairy. I really saw one! Bella didn’t believe me when I told her. She told me I was lying. I’m not a liar, Mama!”

Suva held her breath, waiting for a reaction.

But no reaction came.

Suva exhaled and let her tears fall. Warm against her face which had been cooled by air-conditioning, left tracks to her chin which eventually led to her heart, in her mother’s room. She suddenly felt cold. No more words escaped Suva that evening as she climbed into bed with her mother.

In her imagination, Suva saw her mother’s room as a sort of vacuum, where words became sucked into a hole, deep and dark, which hovered just above her mother as she lay motionless and doubled-up, as if in pain.

She wrapped her arms around her mother and inhaled deeply.

Suva’s mother turned over so their noses touched. Eyes closed, Suva felt her mother’s breathing on her face, she could smell her breath, stale from sleep and then finally, the moist warmth from her mother’s lips on her forehead. It was the first time, since her father’s death, that her mother had kissed her.

***

“The time between the two distances, Rosewood Hall and Kytö’s apartment stretched or shrank depending on whether Layla walked beside him or not. These were feelings Kytö had only read about. In Kytö’s world, these feelings had no purpose. These feelings were rendered obsolete with the advent of mate compatibility testing and procedures which rendered it unnecessary to even need a mate, so when Kytö felt fluttering in the pit of his gut and felt his heart beat faster at even the thought of Layla, he was tempted to seek medical help, but then he remembered the texts he had read and interpreted and studied. These were basic human phenomena, before evolution and science and efficiency changed the rules. Kytö began to embrace these feelings and as a consequence, Layla somehow felt a kind of transference. She too experienced the same hormonal led feelings towards Kytö. Soon they became inseparable.”

“Is this what you would write about us?” Layla asked. It was the weekend and the project was finally complete. There were no pending assignments. It was mid-morning and they were both still in bed.

“Yes, it is important to document this, don’t you think? This is a significant part of my life, you are a significant part of my life.”

Layla yawned, “I suppose so. But why do you write in the third person, Kytö? You should write it like a diary, that way it is less likely to become just a story, a fiction.”

“It’s a good point. But I like that we become characters in a story. Almost stuff of legend, a myth. I wonder how many of us there are who have managed to ignore the conditioning, the societal norms and fall in love, like us.”

Layla smiled and pulled Kytö’s face to her own. She kissed him on the tip of his nose and closed her eyes. “I like that, Kytö and Layla, like Merida and Kes, stuff of legend,” she said as she gently fell back to sleep.

You’ve got a lot of work done!! I’ll read this with full attention and reply 🙂

You’re wonderful! Thank you! There are a few inconsistencies so if you’d like, you could point them out.

Hello! So, I’m back, only a week later! I’m sorry I took so long…

Listen, I absolutely love the parellelism, the warmth, the broken-hearted feel and childhood in Suva’s world, in contrast with Kytö’s cold, innocuous, about to burst, authomatic word.

As I read out loud, Suva’s parts were soooo speech like it felt close to me, which I find special. Towards the end, with Kytö and Layla, it felt rushed, as most of the writing behind is visual and layered, phased, leading us to assume some parts. Their relationship is inferred when she appears but as Layla interferes in Kytö’s action, everything happens faster, they are talking, they are touching, there is questioning, there is social connotations of this futuristic world, and we’ve only met them both. It’s defenitley something to develop and dig further on 🙂 Can’t wait to read about that fairy, I love me some fantastic and science fiction crossover!!! I’m totally following this story!

Hi! Thank you for your response. I really am grateful that you took the time to read and comment. Your comments are invaluable. I agree, Layla and Kyto do seem rushed, I suppose I’m still stuck in short fiction mode and this is one of the only things about the story, I am sure about. I will probably edit it in the subsequent draft. In the meantime, check out Merida and Kes… a legend of my own making. Again, a lot of edits needed. Some of it doesn’t read too well, but at least I’ve got some content. THANK YOU, again…I really do appreciate your opinions.

Hey! Fall in love with it and give them a past and a destiny 🙂 you’re great at this, give it enough time. I’ll check Merida and Kes, for sure! I’ll come by every other day.

Hi! So, it’s a rainy night in Lisbon and on the train back home I remembered your story and decided to read it again! How is this going?

If you don’t know by now, I’m a fan of your writing!

Hi! I’m lost, to be honest. In a good way, I think. I’m back in my hometown in the UK and I’ve been soaking up the love, attention and familiarity one can only find in one’s maternal home. I’m itching to resume writing again. Readers such as yourself are my catalyst. This was a timely jolt along with a few others I’ve had these past few days, that I have a job to do and opportunities like the one I have been given only come around once. I am a writer, I must write. Thank you for being there!

I’ll be right here! Say hi to the UK for me

Hi again! 🙂 i’ve been trying to write some stories and this is one of the three, so far… I’m not sure if it qualifies as short-story, but still, if you ever have the chance to read it, I’d be glad. Keep up the fantastic writing!

https://goncalojuliao.wordpress.com/2016/01/01/whats-on-your-mind/

I’ve read it. It blew my mind, stopped my heart! How can you admire my writing when you write like that? I’m now a fan of yours! Simply amazing. If I were to look for fault it would be to try to deconstruct something for the sake of itself. I do not want to look for mistakes or suggest improvements because as a whole it worked. Simply, wow!