There is an elderly lady who lives in a small but adequate flat in the Begumpet locality of the city of Hyderabad. She is surrounded by her family; her son, her daughter-in-law and her two grandchildren.

She wears a red sari and her hair is white. Her skin is the colour of cream and her edges are soft and rounded.

As she talks to my mother-in-law, I sit slightly bored, trying to take in the conversation in a language I only have a second-hand familiarity with. Telugu, notoriously difficult, doesn’t feel as if it has become any easier with time, and I lose the thread of what is being said, as easily as drifting off into a dream.

We are visiting my husband’s cousins because we are in Hyderabad and this is what we must do.

I rarely bother with what is being said unless it is followed by raucous laughter and then I say, almost timidly, “What? What happened?” and they oblige me with an answer.

This time around we have my own cousin with me, from my mother’s side. Her mother is English, proper, white and her father is my maternal uncle. He is of Bengali origin and setting foot in India since coming to England is an idea he has discarded. No need to look back, I think is what he says. My cousin, therefore, is somewhat confused. She looks like an exotic princess, in either land, I suppose. Fair skinned, dark haired, unmistakably different, tall, slender and doe eyed. I imagine when people look at you differently and you celebrate Diwali and are exposed to little windows of another culture that is supposedly yours, you crave for a deeper sense of it. So she’s here with us and we sit in my husband’s family’s flat eating deep-fried snacks and sipping sweet gingery chai, immersed in a language that I can get only through inference.

And then my husband walks in and he utters something incomprehensible and he opens a cabinet packed with books. The books have yellowing pages and covers which look in danger of crumbling and I walk over straight away.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“This is my aunt’s PhD,” he replies, lifting up a tome worthy of ancient legend. I am immediately excited. My boredom is broken and I ask a barrage of questions.

I am excited because if a woman from a traditional orthodox Indian background is able to pursue something important to her and seemingly unimportant to anyone else, surely I should be able to as well. I suppose it’s that itch again.

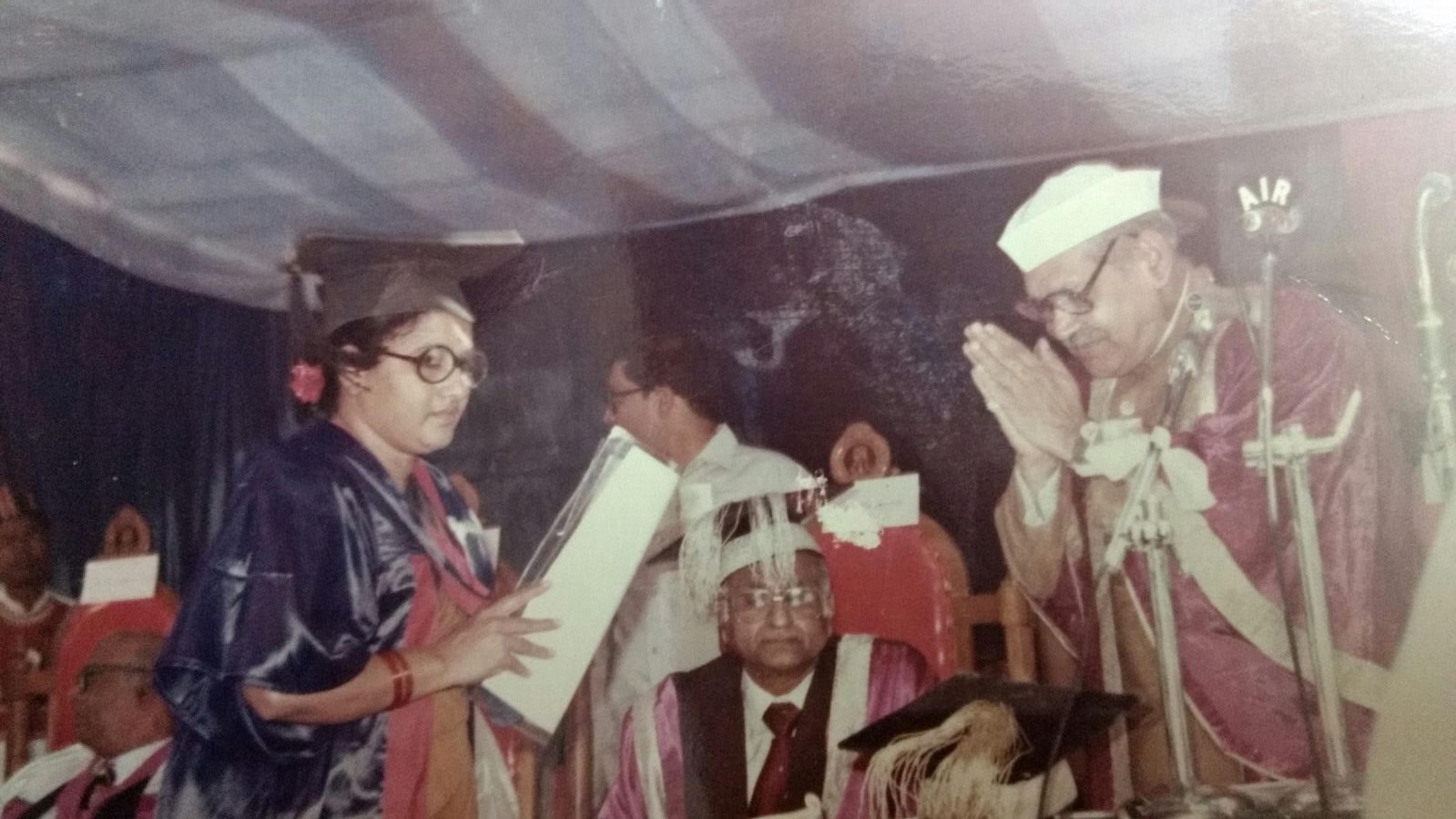

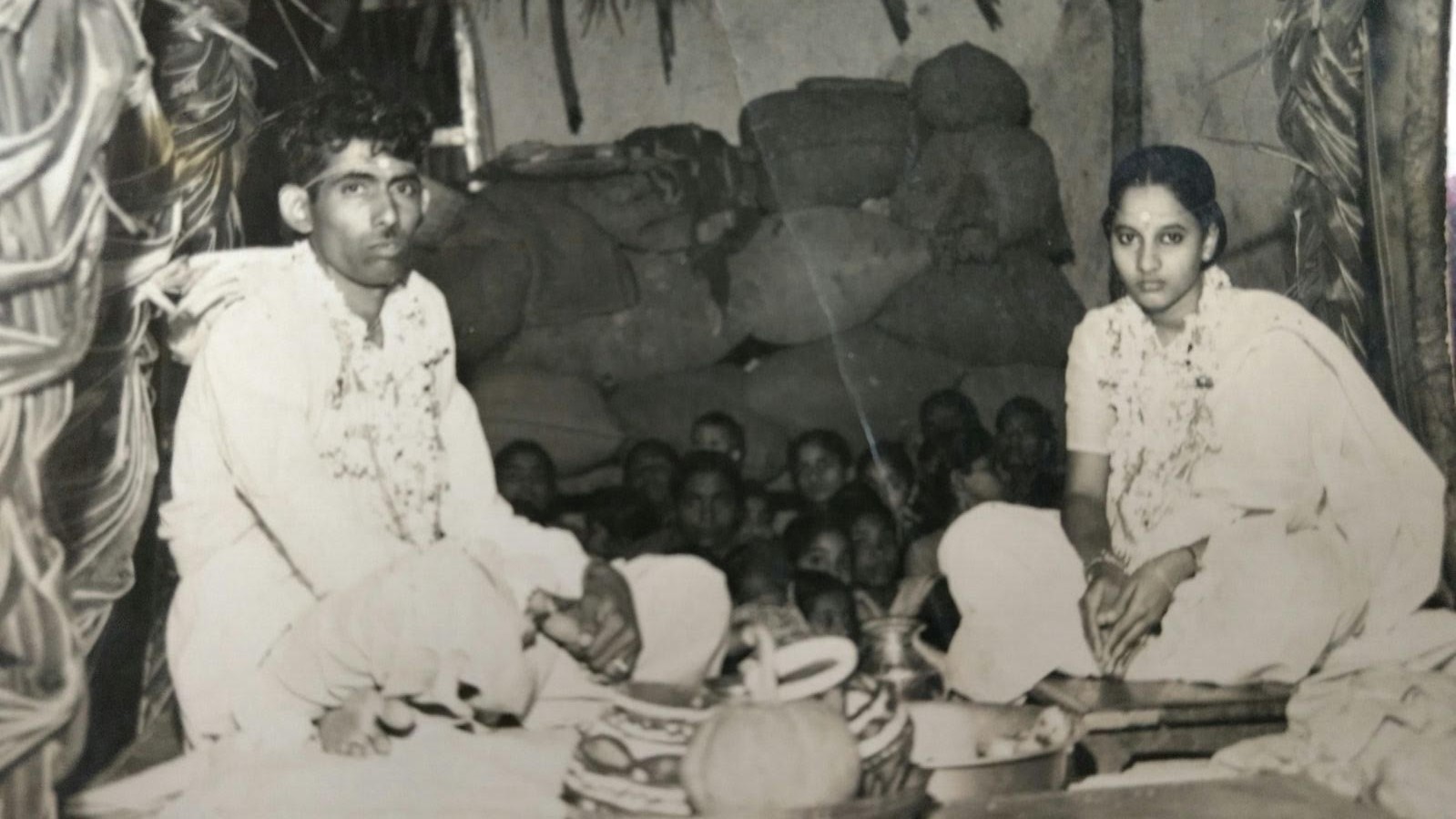

Suddenly the old lady’s son walks in and his wife. The granddaughter is there too and before we know it we are looking at photographs of days gone past. The old woman takes out an album and searches for a picture of when she was formally awarded her PhD. Her eyes shine with pride and she chuckles when we tell her that she was beautiful when she was younger. We see her marriage photos and I am told that she and her husband met in high school and fell in love. Soon after marriage, I believe she and her husband went to pursue their PhDs in the North of India.

We also see a picture of my husband when he was just a boy and we see my mother-in-law skinny and young. There’s even a picture of my daughter, which we must have sent to India at some point when she was less than a year old.

We’re brought together with the stories these images hold and I feel finally a part of a world I struggled to understand. We decide to take some more pictures and surely one day we’ll find them when we’re old.

Briefly we’re bound with old photographs from plastic bags, too numerous to sort into albums. To be able to physically hold and pass around and to remember is something we won’t be doing so much in the future.

Our images are all stored digitally, in my case on Google Drive or Facebook and they are less, these days of people and more of an attempt to ‘artify’ the landscapes I find myself in. I wonder if I am losing out on something. I should capture more of those candid moments which will remind us of who we once were.

Selfies are one thing, a stylised image of how we imagine we would like to be seen, with bigger eyes, a thinner jaw line, all because of the angle or apps at our disposal but a certain authenticity is lost. Photographs of ourselves have become exercises in vanity. They are discarded instantly if we do not look like the image we have in our minds of ourselves. They have become less about the memory, the landmark and more about the impression.

Or was it always this way? Nostalgia is such a wonderful filter to see the world through, perhaps just as illusionary as the filters we use on our camera phones.

Accepting PhD

Marriage

PhD

The lady in the red sari is Dr Lalitha Kumari

Fascinating and really interesting…my grandchildren despite being social media addicts, are often drawn to my photo albums of past decades. I wonder if we will develop a way of sharing our lives captured on our phones with maybe a little more depth? Mmm Happy New year!

Thanks Trees! Happy New Year! There is something about the physical image, isn’t there, that cannot be replicated by the virtual. We need to hold it in our hands, move it closer to our faces, pass it around. Physically sharing a memory, holding a memory is so very precious.

Absolutely loved this post Devs. Like you, I struggle with the idea of pursuing what I feel is only important to me and no one else in the family (writing) or am I using this line to cover up my laziness? I don’t know…but I’m glad you wrote about it.

And wow to “Nostalgia is such a wonderful filter to see the world through, perhaps just as illusionary as the filters we use on our camera phones.” I find myself nodding in agreement to the vanity of ‘ariftying’ every click;)

Happy New Year. xx

Thanks Arti! As always, you’ve been very kind. I love your photographs, by the way. You’ve made them art, and I don’t mean in a vain attempt to artify, you succeed in making it art. Keep clicking and writing, please!